We strive to make a huge amount of positive change through our apps and products, however, it also relies on consumers to change and maintain new behaviours.

Our experience spans behaviour change across a host of different areas, from encouraging people to adopt a new type of exercise and stick with it in the case of our O2 Touch app, to changing the way they book and return to donate blood with the Blood Donor app.

The cumulative effect of millions of people successfully enacting change for good creates large scale impact, which is why 3 SIDED CUBE exists.

)

Itʼs acutely important right now, given that the priority for the tech for good space is centred around climate change and the environment. Innovation in this area means designers and product teams must grapple harder than ever before with how to overhaul entire lifestyles.

So our understanding of how to help people along the journey of integrating beneficial new practices into their lives (and sustaining them!) underpins our productsʼ success.

This post covers three essential concepts that inform our work in the field of behaviour change, however, its only the first in a series I plan on writing to fully explore and understand behaviour change in more detail.

)

Source: Persuasive design: nudging users in the right direction.

Before we seek to change behaviours

Products that change our behaviour are not always beneficial. Designers armed with habit-forming tools and techniques have, in recent years, wrought apps and services that invoke anxiety and addiction.

Social media is the clearest example, and itʼs telling that these platforms are now seeing a backlash and increasing awareness and demand for ethical design is taking hold as a result. But not all examples are as clear-cut and determining whether the change a product strives to make is a virtuous one is a murky area and open to debate.

One important question, however, gives us a practical measure in this area:

Is the change you are nudging users towards a change that they actually want?

Some of the effective nudging tactics used by digital products such as repeated notifications and persuasive language are emotive and command our attention.

If this is helping them strive toward a desired change, it has the potential to be like an encouraging coach pushing them towards their own goals. If they donʼt innately want to make a change, however, these things are coercive and manipulative.

The author of Hooked: How To Form Habit-Forming Products, Nir Eyal proposes this ‘regret testʼ as something we should always ask before crafting behaviour change products.

If people knew everything the product designer knows, would they still execute the intended behaviour? Are they likely to regret doing this? -Nir Eyal, author of Hooked: How to Build Habit-Forming Products.

How hard is behavioural change?

The short answer is; it’s easy to set an intention or even start but incredibly hard to sustain. At the month of publishing this article, February, our annual collective resolve to better ourselves has likely just about fizzled out.

The change we want manifests itself in New Yearʼs resolutions which are deflatingly short-lived according to statistics. One example suggests that only 8% of people succeed on them and data from Strava showing exercise efforts lasting all of 12 days into the New Year.

Why People and Psychology Make Change So Hard…

Knowing the benefits doesn't work

Intuitively, behaviour change struggles should be easily remedied with a clear, factual reminder of the benefits of the change. ‘If you quit X you’ll live Y years longerʼ or ‘you’ll save X amount of moneyʼ.

Appealing to rationality, however, has repeatedly proved ineffective in spurring action as seen in the variously ignored public health campaigns to make people exercise more and stop smoking. In fact, the whole school of thought that believes people make rational choices that might benefit them has a name, ‘naive realismʼ.

Even when we know all the right facts and have the best of motivations, time and time again, behaviour change fails. Rare as they are, behaviour change success stories do exist and they often harness a few key techniques and concepts shown to help.

Naive Realism — each one of us thinks that we see the world directly, as it really is. It’s the unconscious belief that everyone else is influenced by ideology and self-interest, except me. I see things as they really are. Excerpt from “The Happiness Hypothesis” by Jonathan Haidt

1. The strategy of starting small

Knowing that change is hard and willpower is fallible, it makes sense to focus first on simply establishing a habit and build gradually. Overly-ambitious goals for the change you want to make can be daunting and the reason why people drop-off a few weeks in.

This school of thought is expounded by Stanfordʼs Behaviour Design Lab director BJ Fogg who argues that a ridiculously low bar makes starting a new habit more likely.

It should be such a minuscule change to your current behaviour that it is impossible to not start, with his example for tooth flossing being that your change should start with flossing just one tooth then celebrating that action wildly to create a positive feedback loop.

.

You declare victory. Like I am so awesome, I just flossed one tooth. And I know it sounds ridiculous. But I believe that when you reinforce yourself like that, your brain will say yeah, awesome, letʼs do that. - BJ Fogg - founder of the Behavior Design Lab at Stanford University

This approach is echoed in the popular habit creation app, The Fabulous where the challenge for the first three days of your new habit is to merely drink a glass of water when you wake up.

)

Source: App Store: Fabulous – Daily Motivation.

2. Social proof works

The impact of social conventions on our behaviours is hard to overstate. Humans have evolved as social creatures, seeking co-operation and avoiding isolation from groups in order to survive. When change-makers are creating products or services, showing positive rates of compliance has been shown to make a difference.

The American utility provider OPower is one such example. Their experiment of displaying the stats on how customerʼs energy usage compared with their neighbours on paper bills proved to steadily reduce overall consumption and, most importantly, maintain it (even when the experiment ended and the comparative usage was no longer shown).

Another supporting study examined a hotel aiming to increase towel re-use amongst guests. They tested different messaging on three types of sign:

#1. Urged customers to save the environment

#2. Stated that most hotel guests re-used towels

#3. Stated that most guests in their particular room re-used towels

The least effective was the first sign with the second and third (with social proof elements) showing increases in success rates of 26% and 33% respectively.

)

Source: Psychology Today: Changing Mind Changing Towels.

3. Simple micro rewards

From the earliest years of school, we are conditioned to be rewarded for good behaviour. House points, merits and certificates were systems that coached us (well, some…) to complete homework and put in extra effort. They were a form of gamification, which at a more sophisticated end of the spectrum, is what modern, video games use to make them some of the most immersive and habit-forming products in the world.

What’s interesting is that it seems that, like a paper house point sticker, rewards can be pretty basic in proportion to their impact.

Take the example of Norwayʼs approach to getting people to recycle more plastic bottles. They use reverse vending machines that give a few pennies back to the consumer for depositing their used bottles. Itʼs incredibly simple and the cost to run relatively small (when the value of the material is factored in) but has achieved mass behaviour change and an incredible 97% of plastic bottles going back into the chain to be reused.

)

Source: Norway’s Successful Plastic Recycling System.

Looking at these simple machines through the lens of interaction design, you start to see why they might work so well. The instant feedback, in the form of your coins dropping into the tray, as a result of your good deeds and the associated feeling of a small win makes it a positive, immediate and tangible experience. More elaborate machines enhance this feedback with screen interactions and animations that react to each item added and give you the chance to choose a charity to donate your reward to.

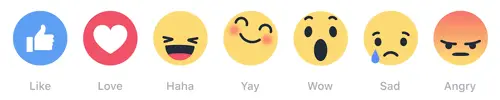

And actually, a satisfying piece of interaction design can be a big incentive for users to complete certain actions in an interface. Facebookʼs ‘reactionsʼ feature was introduced back in 2016 with a stated goal of allowing more expression but a tacit one of harvesting more sentiment data to create feeds that better resonate with each user.

)

Source: Facebook Reactions: Not Everything in Life is Likable.

They went through an extensive design process to hone a playful and delightful flow of that nudges users to impart their feelings on posts. Reactions use vivid colour and characterful animations (tactics from the playbook of attention-grabbing design the platform is now infamous for) to lure us in followed by a satisfying pop and colour change as you tap, celebrating your action and affirming your emotional response to the post.

Tactically employed surprise and delight is ubiquitous in apps, Deliveroo uses a similarly enjoyable confetti animation to slap you on the back for tipping their riders and the Clear appʼs smooth motion design makes ticking items off your to-do list incredibly gratifying. This is a powerful nudging technique that works. Facebook reactions have seen a massive uptick in usage since their launch – they have managed to affect a sustained change in behaviour on the platform – essentially with some nice animation.

The nuances of behaviour change

When we start to think about the different contexts, subject matters and associated benefits for users and society, rewarding products and design have a huge potential to change behaviours for the better.

But each area has it’s own nuances, tactics and messaging that work slightly more effectively within it.For example, changing behaviours relating to recycling would take a completely different approach to changing people’s behaviour with adopting exercise.

Climate change is the most acutely relevant example right now and the next part of this series will look at the mental models that affect how people process it and a potentially controversial concept that might help us address it.

If behaviour change is something that interests you or you can see the potential tech can have in creating a positive impact, get in touch with our team!

Published on 25 February 2020, last updated on 15 March 2023

)

)